Ben Liu is a minimalist — and on this warm, stuffy afternoon, he’s also late to our meeting.He sends me a text not long after I tell him I’ve arrived (“Let me get my ass off my bed.”) I manage to find seats upstairs, on the second floor, in a quiet corner where two people can have a conversation. I wanted to talk to Ben for several reasons: he was a self-proclaimed minimalist who’s been practicing the art-of-owning-little for quite some time, based on his Facebook page,

Minimalism in Singapore.

Meeting Ben, The Minimalist

Upon our first handshake, Ben seemed a genuine, friendly guy with nothing to hide. He had a zen, monk-like vibe about him, with a head shaved bald and a simple, functional-looking fashion sense. He gave me the feeling that he really

was a minimalist, the kind you’d see on YouTube living a simple, quiet existence and always radiating calm energy.That is, until he opens his mouth.

“Is this a formal or informal interview ah?” he asks, somewhat loudly.

“Uh, we’re keeping it casual,” I say, trying to minimise my shock.

His eyes light up with… relief? “Okay, good.”

He takes his place beside me, flopping down into the chair in the way one does when they come home after a long day at work. He’s loud, chummy, and if I’m being honest, a little

beng.

Yet somehow, I feel like we might have been friends for years.

At 36 years old, Ben is living on his own in a rented room at Balestier. He’s been living on his own for 13 years, having moved out at 23 following his parents’ divorce. His first brush with minimalism was around then, when he realised he didn’t want all these possessions he owned as he was moving out.

It was awareness that made him a minimalist — an awareness of all the

things he’d accumulated over the years, and an awareness that he didn’t want to be encumbered by those

things anymore.

One day, a friend noted to him that he lived like a minimalist, and handed him a book on the topic. Ben recounts to me that the moment he read it, he knew it instantly: this was him.

He describes his room and possessions to me in about 30 seconds.

There’s a window and a cabinet with all my documents, electronics, and everything. I also have toiletries and medicine, which is very important. Medicine is the only thing I hoard, like for

laosai and stuff like that. Other than that, I own some hardware for repairs in case I need to patch things up at home.”

He indicates the toilet behind where we’re sitting. “All my stuff can fit into that small space.”

Ben’s daily routine is simplified enough that he doesn’t have to expend a lot of mental energy on decision-making in the early hours, a result of his minimalist take on life.

In the morning, he eats the same thing for breakfast every day: instant oatmeal that’s sometimes mixed in with his daily morning coffee if he’s in a rush. Getting dressed isn’t an issue for him either.

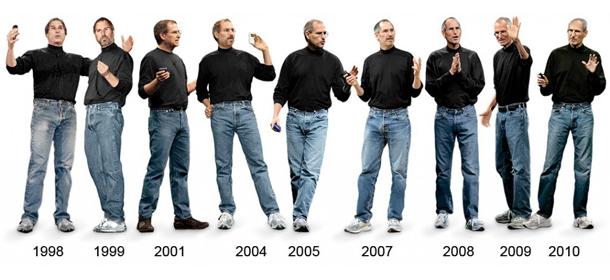

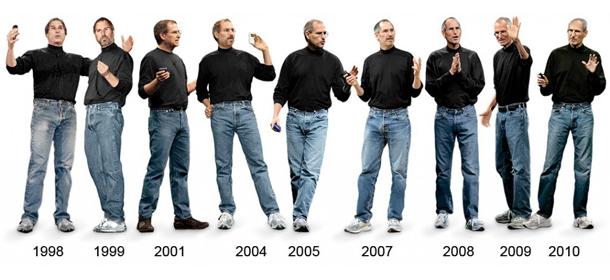

His philosophy to a minimalist life involves cutting down on decision-making for the everyday things. “We can free up that mental capacity, just like Jack Ma or Mark Zuckerberg,” he says. “They come from simple beginnings.”

We briefly discuss extreme minimalism where people choose to only wear one piece of clothing for a week and only sleep on the floor.

But that’s not Ben’s minimalism.

“I embrace the middle ground,” he says. “When I buy things, I think about whether they’re value for money and whether I love them. If I do love them, will they last? Do they look good?”

To prove his point, he shows me his messenger bag and tells me it cost him $700.

How Does a Minimalist Spend His Money?

I was a little blindsided. Like my first-impression of Ben, my impression of minimalism was dashed. Minimalism — or perhaps the version that Ben practices — did not seem equate to extreme frugality.

But I asked him about how the lifestyle changed the way he spent his money. He shared that he spends a minimal amount on food, but doesn’t shy from indulging every once in a while with friends or dates, though he does try to keep things simple on a day-to-day basis, like with the abovementioned oatmeal.

“For my expenses, I cut expenses by figuring out how to get free meals, like helping out at a friend’s restaurant,” he says.

Then we jumped on the subject of clothes, and what was inside his wardrobe.

He lists it out for me plainly: Seven pants, two berms, seven shirts, seven pairs of socks, and seven pairs of underwear

“I no longer go to places like H&M,” he says. “I buy very functional stuff nowadays.”

I asked him if he only went shopping to replace shirts or pants that finally give out over time. He laughs and indicates the hem of his grey shirt, somewhat cheekily. “I have one shirt that has a hole here, but it’s a black shirt so nobody can see it.”

He tells me his dark green pants with a khaki feel to them were bought for $12 at the unlikeliest of places for good fashion: Mustafa.

“It’s my favourite place to shop,” he tells me. “I also visit thrift stores, pick up a pair of Levi’s for $15, and alter them into berms. They’ll look brand new, and nobody will give a shit.”

But that doesn’t mean he goes cheap all the time. Despite preferring second-hand items, he still prioritises quality over quantity.

“I still choose expensive quality items because they last longer,” he says. But he never gives in to the big brands that reign supreme. He also avoids fast-changing trends and hyped-up brands.

At this point, he stretches out his legs and indicates the hardy-looking shoes he’s wearing, like something you’d find from a Redwings catalogue. “These shoes have been with me for over a year and a half, and they still look good — they cost $600.”

He points out at a young guy seated nearby.

“Sneakers like Yeezys don’t last. But mine? Just remove the soles when they wear out and slap on a new pair.”

He fishes out his phone and opens up Instagram. His personal feed is 90% shoes — exactly the kind he’s wearing. This is a personal project of his, where he resoles old shoes to make them look brand new and wearable again.

“Nobody gives a shit about what you wear, day after day,” he later says, as we continue to talk over coffee. “So why are we buying things to impress people who will never be impressed with us?”

What Sparks Joy?

When a lull in the conversation occurs, I jump on the chance to ask the question I’d been burning to ask since we met. “So what do you think of Marie Kondo?”

Ben responds, “Her style is really cool, but it’s not minimalist. But I know people can find a sense of happiness from it. It’ll make your life more functional.” He references the KonMari method, where one identifies and lets go of old possessions that no longer spark joy. We discuss the emotion behind refusing to let things go and hoarding, and come to the conclusion that hoarders were never taught how to let go.

I nod, understanding. “It’s fear and anxiety that’s stopping them from letting go, though.”

“It’s fear of the unknown,” Ben points out. “What you need to do is to really embrace the item, understand it, and finally let it go if it no longer adds value to your life. It’s simple.”

So, not all that different from the famous KonMari method.

Ben takes the chance to share with me a golden rule of his: If he doesn’t touch an item or possession for nine months, he’ll give it away — provided it’s still in its original condition.

“I’ll put things in a black trash bag, tie it up, and label it with a date,” he shares. “And if I haven’t opened up the bag by then, I’ll know it’s time to let it go.

“Certain things have shelf life. I have a friend who used to move these unused items of hers back and forth, from place to place, over eight years.” He gestures with open palms. “She could have used all that time to do other things.”

Do you have the same approach for friendships?” I ask him. “Do you declutter those too?”

“Yes!” he responds, nodding. “I feel like you need to close one chapter to arrive at the next. There was someone I knew who was very toxic, who didn’t make the friendship productive at all, so I just cut him off and left very quietly. There was no point staying in touch with him.”

Ben also candidly mentions that he’s been dating around, and takes a very “easy come, easy go” approach with his partners. He acknowledges that it can sometimes be seen as crude, but “life is too short for encumberment,” he says.

But as I soon discovered, there are exceptions to this approach. A big part of minimalism seems tied to the act of decluttering, but not everything can be gotten rid of.

“With my father, I have a toxic relationship with him, but I’m still working on it. I can’t declutter that.”

There’s a window and a cabinet with all my documents, electronics, and everything. I also have toiletries and medicine, which is very important. Medicine is the only thing I hoard, like for laosai and stuff like that. Other than that, I own some hardware for repairs in case I need to patch things up at home.”

He indicates the toilet behind where we’re sitting. “All my stuff can fit into that small space.”

Ben’s daily routine is simplified enough that he doesn’t have to expend a lot of mental energy on decision-making in the early hours, a result of his minimalist take on life.

In the morning, he eats the same thing for breakfast every day: instant oatmeal that’s sometimes mixed in with his daily morning coffee if he’s in a rush. Getting dressed isn’t an issue for him either.

His philosophy to a minimalist life involves cutting down on decision-making for the everyday things. “We can free up that mental capacity, just like Jack Ma or Mark Zuckerberg,” he says. “They come from simple beginnings.”

There’s a window and a cabinet with all my documents, electronics, and everything. I also have toiletries and medicine, which is very important. Medicine is the only thing I hoard, like for laosai and stuff like that. Other than that, I own some hardware for repairs in case I need to patch things up at home.”

He indicates the toilet behind where we’re sitting. “All my stuff can fit into that small space.”

Ben’s daily routine is simplified enough that he doesn’t have to expend a lot of mental energy on decision-making in the early hours, a result of his minimalist take on life.

In the morning, he eats the same thing for breakfast every day: instant oatmeal that’s sometimes mixed in with his daily morning coffee if he’s in a rush. Getting dressed isn’t an issue for him either.

His philosophy to a minimalist life involves cutting down on decision-making for the everyday things. “We can free up that mental capacity, just like Jack Ma or Mark Zuckerberg,” he says. “They come from simple beginnings.”

We briefly discuss extreme minimalism where people choose to only wear one piece of clothing for a week and only sleep on the floor.

But that’s not Ben’s minimalism.

“I embrace the middle ground,” he says. “When I buy things, I think about whether they’re value for money and whether I love them. If I do love them, will they last? Do they look good?”

To prove his point, he shows me his messenger bag and tells me it cost him $700.

We briefly discuss extreme minimalism where people choose to only wear one piece of clothing for a week and only sleep on the floor.

But that’s not Ben’s minimalism.

“I embrace the middle ground,” he says. “When I buy things, I think about whether they’re value for money and whether I love them. If I do love them, will they last? Do they look good?”

To prove his point, he shows me his messenger bag and tells me it cost him $700. Do you have the same approach for friendships?” I ask him. “Do you declutter those too?”

“Yes!” he responds, nodding. “I feel like you need to close one chapter to arrive at the next. There was someone I knew who was very toxic, who didn’t make the friendship productive at all, so I just cut him off and left very quietly. There was no point staying in touch with him.”

Ben also candidly mentions that he’s been dating around, and takes a very “easy come, easy go” approach with his partners. He acknowledges that it can sometimes be seen as crude, but “life is too short for encumberment,” he says.

But as I soon discovered, there are exceptions to this approach. A big part of minimalism seems tied to the act of decluttering, but not everything can be gotten rid of.

“With my father, I have a toxic relationship with him, but I’m still working on it. I can’t declutter that.”

Do you have the same approach for friendships?” I ask him. “Do you declutter those too?”

“Yes!” he responds, nodding. “I feel like you need to close one chapter to arrive at the next. There was someone I knew who was very toxic, who didn’t make the friendship productive at all, so I just cut him off and left very quietly. There was no point staying in touch with him.”

Ben also candidly mentions that he’s been dating around, and takes a very “easy come, easy go” approach with his partners. He acknowledges that it can sometimes be seen as crude, but “life is too short for encumberment,” he says.

But as I soon discovered, there are exceptions to this approach. A big part of minimalism seems tied to the act of decluttering, but not everything can be gotten rid of.

“With my father, I have a toxic relationship with him, but I’m still working on it. I can’t declutter that.”