Investing | Article

Why We Hate Investing

by Sophia | 4 Jul 2019 | 7 mins read

Mention the word “investment” and Laura’s mind will immediately associate that to “gambling”, and her enthusiasm drops to sub-zero temperatures. Investments might be the way of the world, but it’s not for 24-year-old Laura. At least, not for now.

Laura learned from a young age what it was like to be burned financially, watching her father suffer losses he couldn’t handle. Even though she was a child, she understood what was happening to her family.

When we were young all we knew about ‘investing’ was something to do with losing money, the word “shares”, and mum & dad fighting.

Her parents argued about the losses from investments occasionally, with Laura as their lone spectator.

“But we made it work with less money,” she said, reflecting on her growing up years. “We survived. So my response to it all was kind of just… que sera sera.”

Of stocks and soccer

Her father dived into investments as well as soccer betting for a time. Needless to say, the soccer bets didn’t come through – and neither did his Singaporean and Malaysian stocks and shares.

“I wanted to make money quickly, so I invested in shares that were quite risky,” he said (preferring not to be named). “Bank interest was low, so why keep money in a bank that can’t grow it?”

According to Laura’s father, his calculated risk “went beyond expectations.”

What’s worse, he traded stocks using the now-defunct Central Limit Order Book, a secondary market in Singapore that allowed investors to trade Malaysian stocks. In 1998, to stem the ravages of the Asian Financial Crisis, the Malaysian government banned overseas trading of Malaysian shares, forcing many local investors to sell their investments at heavy losses.

Laura’s father made a 50% loss on his initial investment.

This didn’t plunge the family into extreme poverty, but times were rough for a while, up until Laura turned 15. “We were broke for a long time,” she said.

“In primary school, my mother cooked a lot – because we couldn’t afford more expensive meals for dinner,” Laura recounted. “But by the time I hit secondary school, my dad was working for Changi Airport, so it wasn’t all that bad by then. We managed to stay afloat – and cleared off debts for good around that time.”

Despite this, Laura came away from the experience shaken up about investments. When asked if she would one day invest for her own future, she responded in the negative.

“I’m immediately cautious about it,” she admitted. “I’m scared of ending up like my parents that I’m even resistant towards using credit cards. That was also one of the bigger issues that led to our financial problems, along with the investments.”

I then asked her what she knew about investments, just to get a feel for whether she was being fearful of the right things – or just shadows in the dark. Laura gave it her best try: “Money goes in. If the factors are right and you’re in luck, more money comes out. If you’re not lucky or the factors aren’t ideal, you lose that money – or even more.”

And the most terrifying thing about investing to her?

“Losing more than I can handle. Or owing people money. And always being in debt.”

It’s probably unsurprising that she has such an outlook on investing. After all, if one’s first experience with investing is suffering losses – or even just watching someone lose their money – it’s only natural that they’re cautious or avoidant about it altogether.

Laura’s story is nothing new. Like many millennials in my office, or even you reading this, we might have been taking our PSLEs during the 2008 financial crisis.

Older millennials might also remember the 1997 Asian financial crisis.

During crisis times, newspapers headlines talk of plummeting GDPs and rising unemployment percentages; but behind these imaginary numbers were real families falling apart.

Something many of us witnessed.

Understandably, these events spawned a generation – like Laura – of young adults highly averse to the word “investing.”

Learning about investments

On the upside, Laura isn’t completely against investing. “I wouldn’t mind learning more about it,” she said.

“But the idea that I might be tempted to earn easy money is scary.”

The idea of ‘easy money’ came from Laura’s father, who believed at the time that investing and pouring some money into soccer bets would make them quick bucks. But quick wins usually come with great risks.

What we need to understand is: that is not investing.

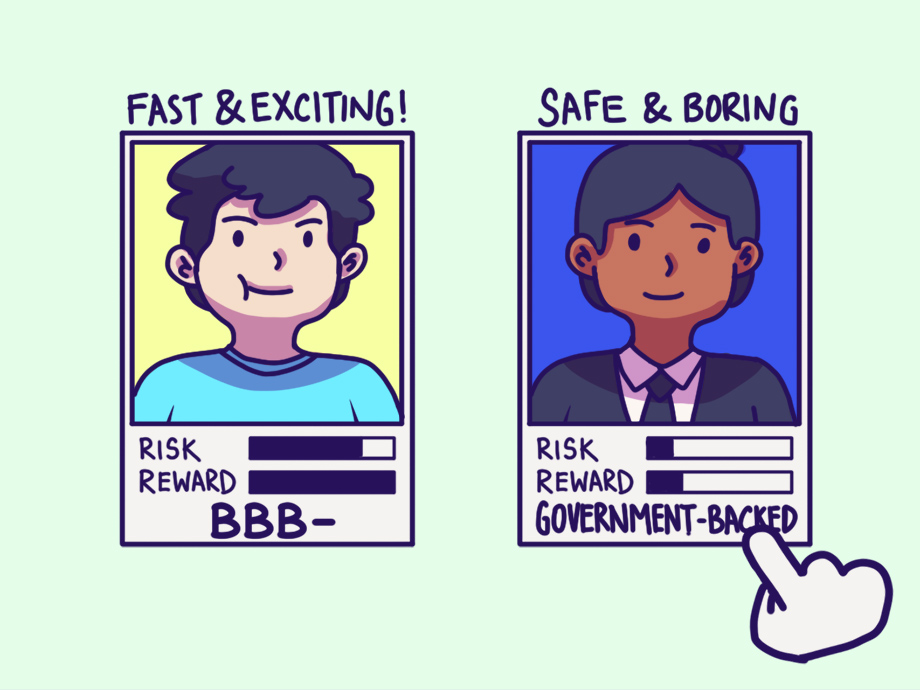

Investing has gotten a bad rep’ throughout the years with people trying to make a quick buck, flipping stocks (or forex) for ‘easy’ profits. It would be more fair to classify these activities as trading.

Usually, disaster strikes harder when traders take on leverage. Essentially, borrowing money to execute trades, hoping to make a quick profit and return the loan afterward.

Of course when the market goes bad, and the lender forces a repayment, leveraged traders get into deep sh*t.

Truly responsible investing has a few very important ground rules

Don’t invest money that you need for the immediate future;

Don’t invest money you’re not prepared to lose.

Build up an emergency fund first

Especially the last point, and we can’t stress that enough. Don’t just pay lip-service to an emergency fund, or get tempted to take just a little risk with it. Stay disciplined and keep it aside at the ready.

Why? Because bad news comes in pairs.

During a prolonged economic crisis, typically, the investor market crashes. Yet – at the same time – the chances of one gets laid off from work rockets higher and higher.

But the economy move in cycles, things will get better, so have the cash prepared to ride out the bad times. Of course, one can get have an invested company implode during a crisis, but again, with a proper emergency fund, that event won’t jeopardize your next meal. You recover, and hopefully learn a lesson on evaluating a stock – if that’s your thing at least.

Changing the narrative

So why is it important to have a change the way we look at investing? Well, simply put, the more we put off investing, the more we harm ourselves.

We must invest. Or at least, find a way to grow our money.

For us wage-slaves, it is close to impossible (or you have to be hyper-frugal) to simply rely on savings for a “typical” retirement at 65. Believe us, we did the math.

And the irony? If we started earlier, we would have had an easier time hitting our long term financial goals (like retirement). Because of all the things we don’t have, what do have is the benefit of time.

The luxury of time

- Investment returns to compound over a longer period

- Longer time frame to ride out market volatility

- Investing aggressively while we have less financial commitments

- Making mistakes early

So as with many things in life, there comes a point we gotta stop blaming our parents and time to start being responsible for ourselves, and the earlier we start taking another look at investing, the easier it will be.