By now, most of us know the

drill: Reach retirement age of 65 in one piece and live off retirement payouts from CPF LIFE. The only way to do that is to build enough CPF savings to meet something called the minimum sum.But every year the CPF minimum sum increases, and outrage ensues. Some think,

Ha! Again CPF shifting the goalposts and locking more of my money away!

More level-headed criticism would be that the minimum sum increments are impossible to predict, adding an element of uncertainty when we do long-term retirement planning.

However, over the last five years, the basic retirement sum (BRS) increase has standardised to an annual increment of $2,500.

| Year |

BRS Amount |

| 2016 |

$80,500 |

| 2017 |

$83,000 |

| 2018 |

$85,500 |

| 2019 |

$88,000 |

| 2020 |

$90,500 |

This fixed increment of the minimum sum was arguably a good thing — the predictability of it made it easier to foresee far ahead, if one has enough CPF savings to qualify for the minimum sums and the payments that we expect to receive in our retirement years.So why does this increase happen? Well, inflation and our life expectancy. We want to be able to afford goods and services when we’re old and grey, and we want to have enough money to sustain us till our dying day. So to boost monthly payouts from CPF, the minimum sums are correspondingly raised.However, predictability was not the main goal behind the increments.

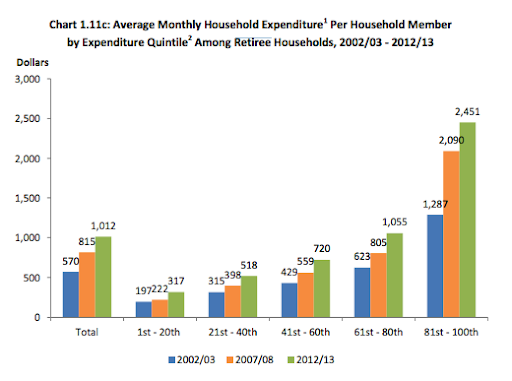

The main objective was to increase the minimum sums by 3% each year to catch up with

lifestyle inflation. Between 2002 and 2014, household expenditure studies found that

lower-middle retiree expenditures rose 5% annually and outpaced inflation.

So in 2015, CPF announced the five-year increment roadmap targeted at members turning 55 between 2017 to 2020. However, the CPF board has not announced the next increment roadmap past 2020.

So the question then is: Would it be reasonable to expect CPF to continue such a predictable increase in minimum sums?

We can look at certain factors to analyse this:

- Has CPF achieved its 2015 objective in catching up with lower-middle income groups expenditures?

- Moving forward, does a fixed increase in the BRS make sense?

Has CPF Caught Up?

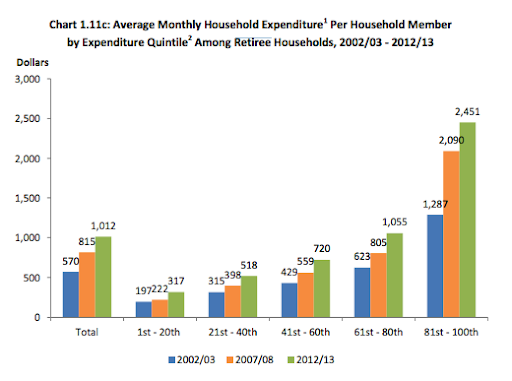

2014’s household expenditure study found that the lower-middle 21st to 40th quintile of retiree households required $518 a month for

basic retirement needs. This is up from $398 in 2008, so CPF’s objective was to fill this gap.

The next question would be, what are the needs of retirees today?

Unfortunately, the most recent household expenditure survey in

2018 did not have the same analysis of retiree spending habits that the

2014 study had. So it is not possible to see if lifestyles have, again, ballooned past inflation.

But if this group’s expenditure has ‘stabilised’, this sum would be almost the same today. This is because core inflation has been effectively

flat — around 0.2% a year — between 2014 to 2018.

So, let’s just assume that $518 is enough to cover a lower-middle quintile retiree’s basic needs, does today’s BRS payouts cover that?

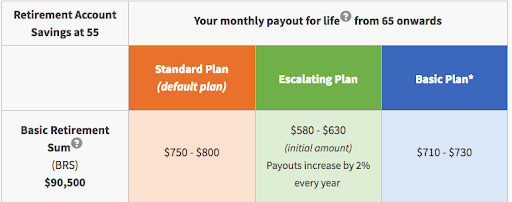

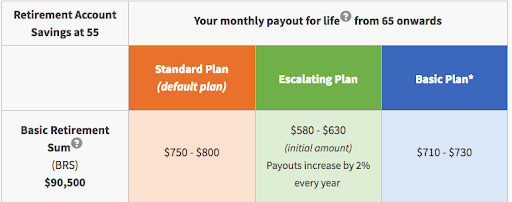

At first glance, under the escalating plan, it seems that the lower bound of today’s BRS $580 payout has caught up with the hypothetical needs of the 21st – 40th quintile.

The escalating plan is inflation hedged, so we picked it because it is the most straightforward plan to ensure retirement security.

The next thing to consider is that under the current CPF LIFE payout schedule, payout figures are locked in at 55

but only start paying at 65. What this means is that even before they begin, the CPF payouts are subject to 10 years of inflation — and might potentially become outdated after 10 years of inflation-eroding effects.

However we (and CPF) cannot assume inflation to be flat in the future, so taking into consideration a theoretical inflation rate 2%* after 10 years — the initial “locked-in” CPF payout needs to be 22% higher than today’s requirements to stay relevant.

To accomplish this, payouts have to be

22% higher than a potential retiree’s needs at 55, to ensure it’s relevant at 65.

This means an increment from $518 to $631 a month. Which we find is still within the upper bound of CPF life’s BRS escalating plan payouts plan.

*2% is a soft inflation “target” that MAS has deemed as a consistent enough to maintain price stability in the economy. Note that this is not an explicit target rate set by MAS.Does a Fixed Increment Make Sense?

Perhaps some inflation is still needed to move the sum to the middle of the payout range of $580 – $630.

The range is there because payouts reduce gradually because when combined CPF balances fall below $60,000 — due to less bonus interest earned on combined balances. Currently, we receive 1% bonus interest on combined CPF balances.

In addition, according to the CPF website:

Payouts may also be adjusted to account for long-term changes in interest rates or life expectancy. But they add that,

Such adjustments (if any) are expected to be small and gradual.

With this in mind, would it be reasonable for CPF to maintain this constant $2,500 increment? — which will help younger Singaporeans plan for retirement — But does it make sense in terms of inflation numbers?

We decided to see what this $2,500 increase a year means in inflationary terms, as the fixed increase equates to different inflation percentages — depending on how far an individual is away from 55.

The following table crunches the numbers, taking into account 2020’s minimum sum of $80,500, then adding $2,500 to the BRS for each year a hypothetical individual is away from age 55.

| Age Now |

Years to 55 |

Increase

($2,500 x Years) |

BRS at Age 55 |

Inflation Rate |

| 20 |

35 |

$87,500 |

$178,000 |

1.95% |

| 25 |

30 |

$75,000 |

$165,500 |

2.03% |

| 30 |

25 |

$62,500 |

$153,000 |

2.12% |

| 35 |

20 |

$50,000 |

$140,500 |

2.22% |

| 40 |

15 |

$37,500 |

$128,000 |

2.33% |

| 45 |

10 |

$25,000 |

$115,500 |

2.46% |

| 50 |

5 |

$12,500 |

$93,000 |

2.62% |

Interestingly, if the yearly $2,500 increase is maintained, it seems a curve is created, inflating the BRS closer towards 3% for those reaching retirement sooner. However, for those that just joined the workforce at age 20, inflation numbers fall closer to 2% per year.

In essence, this curve is steeper for older people if any “catch up” and adjustments are needed, but slowly flattens to 2% for younger Singaporeans — an inflation figure that seems more reasonable in today’s environment.

So perhaps it’s possible that a yearly increase of $2,500 is sustainable. A gradual appreciation that leaves headroom for incremental changes in life expectancy and expenses. But for us younger Singaporeans, it also lends some predictability to the system — barring any huge shifts in inflation in the wider market at least.

Conclusion

But the big question left unanswered: Have retirees’ lifestyles inflated again from 2014 to today? This might spur CPF to relook at the increments again. Unfortunately, because there is no data from the 2018 household income study, we have no idea.

The only indicator we have is a

study conducted last year by the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy that determined a single retiree requires $1,379 a month (!) — a huge jump from $631 a month. However, this was criticised by some to include luxuries such as an annual holiday.

But more importantly, what does the government think about this and how does it define basic living expenses? Perhaps some clues can be gleaned from a

speech by Minister Josephine Teo in November last year.

“With rising aspirations, retirement adequacy is not just a matter of meeting basic expenses” and that

“…CPF must remain a ‘live system’, always evolving and ever-responsive to emerging needs.”

So perhaps a fixed $2,500 increase could be too rigid for such a ‘live system.’

In the end, all this is really speculation and all we retirement warriors can do is wait and see CPF’s new roadmap — or lack thereof — for the minimum sum increases, which should be released sometime this year.

The next question would be, what are the needs of retirees today?

Unfortunately, the most recent household expenditure survey in 2018 did not have the same analysis of retiree spending habits that the 2014 study had. So it is not possible to see if lifestyles have, again, ballooned past inflation.

But if this group’s expenditure has ‘stabilised’, this sum would be almost the same today. This is because core inflation has been effectively flat — around 0.2% a year — between 2014 to 2018.

So, let’s just assume that $518 is enough to cover a lower-middle quintile retiree’s basic needs, does today’s BRS payouts cover that?

The next question would be, what are the needs of retirees today?

Unfortunately, the most recent household expenditure survey in 2018 did not have the same analysis of retiree spending habits that the 2014 study had. So it is not possible to see if lifestyles have, again, ballooned past inflation.

But if this group’s expenditure has ‘stabilised’, this sum would be almost the same today. This is because core inflation has been effectively flat — around 0.2% a year — between 2014 to 2018.

So, let’s just assume that $518 is enough to cover a lower-middle quintile retiree’s basic needs, does today’s BRS payouts cover that?

At first glance, under the escalating plan, it seems that the lower bound of today’s BRS $580 payout has caught up with the hypothetical needs of the 21st – 40th quintile.

The escalating plan is inflation hedged, so we picked it because it is the most straightforward plan to ensure retirement security.

The next thing to consider is that under the current CPF LIFE payout schedule, payout figures are locked in at 55 but only start paying at 65. What this means is that even before they begin, the CPF payouts are subject to 10 years of inflation — and might potentially become outdated after 10 years of inflation-eroding effects.

However we (and CPF) cannot assume inflation to be flat in the future, so taking into consideration a theoretical inflation rate 2%* after 10 years — the initial “locked-in” CPF payout needs to be 22% higher than today’s requirements to stay relevant.

To accomplish this, payouts have to be 22% higher than a potential retiree’s needs at 55, to ensure it’s relevant at 65.

This means an increment from $518 to $631 a month. Which we find is still within the upper bound of CPF life’s BRS escalating plan payouts plan.

*2% is a soft inflation “target” that MAS has deemed as a consistent enough to maintain price stability in the economy. Note that this is not an explicit target rate set by MAS.

At first glance, under the escalating plan, it seems that the lower bound of today’s BRS $580 payout has caught up with the hypothetical needs of the 21st – 40th quintile.

The escalating plan is inflation hedged, so we picked it because it is the most straightforward plan to ensure retirement security.

The next thing to consider is that under the current CPF LIFE payout schedule, payout figures are locked in at 55 but only start paying at 65. What this means is that even before they begin, the CPF payouts are subject to 10 years of inflation — and might potentially become outdated after 10 years of inflation-eroding effects.

However we (and CPF) cannot assume inflation to be flat in the future, so taking into consideration a theoretical inflation rate 2%* after 10 years — the initial “locked-in” CPF payout needs to be 22% higher than today’s requirements to stay relevant.

To accomplish this, payouts have to be 22% higher than a potential retiree’s needs at 55, to ensure it’s relevant at 65.

This means an increment from $518 to $631 a month. Which we find is still within the upper bound of CPF life’s BRS escalating plan payouts plan.

*2% is a soft inflation “target” that MAS has deemed as a consistent enough to maintain price stability in the economy. Note that this is not an explicit target rate set by MAS.