As mentioned, SSBs cannot be traded on the stock market, but SGS bonds can — just like stocks and shares.

But how do you figure out which one to buy? How do you assess them to see which one is worth your investment?

Well first, you have to know where you can look for market data, this can be usually found on your investment broker’s platform, or you can also use MAS’s bond calculator. Here, you can find details of previously issued government bonds, including the original coupon rates, the latest closing prices on the secondary market — and based on the secondary market prices, the calculator spits out the yields you can expect to receive.

(1) Annual yield

Of course, the most important thing to assess with any investment is your profit, and as we went through earlier, annual yield refers to the actual returns you’ll get on your investment each year.

So here it’s simple, the higher the yields the better.

(2) Below par

Par value, as we have also mentioned, means the real maturity value of the bond, in SGS bond’s case, expressed in multiples of $100. So if you find a bond selling on the market at a price of $90, this means the bond is priced below-par.

Because the par value will be returned at maturity, so if you manage to pick up a bond with a total par value of $1,000, but at the lower price of $900, you can expect a profit of $100.

This ‘bonus profit’ is on top of the annual yield you would receive from the bond.

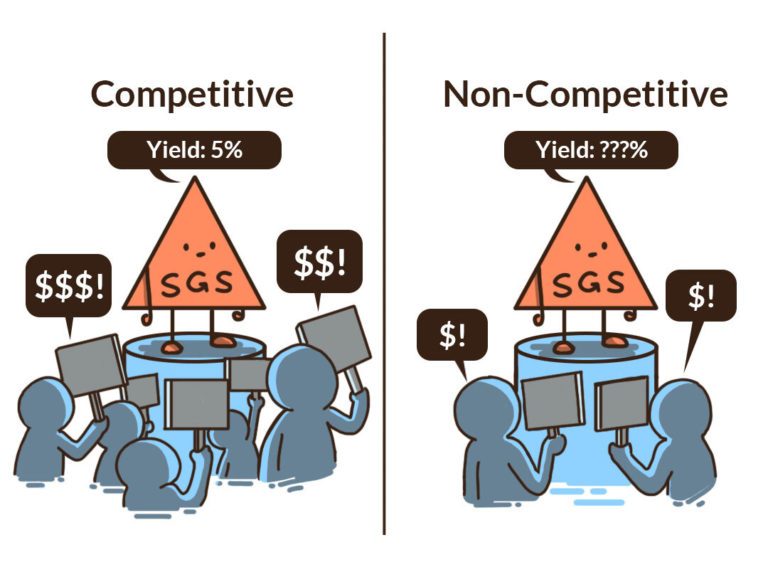

Because of the ability to be traded on the market, there might be opportunities to find SGS bonds that are priced lower (or higher) on the stock market than what was originally issued on the primary market.

But this does not mean below-par bonds are an automatic buy, if you see a swath of low-priced SGS bond, it could just mean that newer SGS bonds being issued on the primary market have better coupon rates or yields compared to older bonds and bills — and the prices on the secondary market have to drop to stay competitive with the new bonds-on-the-block.

Or perhaps, investors could be selling their bonds at a discount to pull money out of the bond market quickly, in order to redeploy their capital into a roaring stock market.

As you can see, it’s SGS bond investing is not so straight forward, and you have to understand the investment market holistically to be an effective investor in SGS bonds!

(3) Dirty vs Clean price

If you clicked on the MAS link above, you might have come across the term ‘dirty’ price.

While this does not really factor into calculations on whether a bond is worth investing in, but it’s still a term fledgling bond-investors should get familiar with.

The term refers to the accrued interest that a buyer has to compensate the seller for the upcoming coupon disbursed by the bond. As such, the dirty price rises when the bond is traded closer to a bond payout date, as more accrued interest has been ‘stored up’.

The ‘clean’ price refers to the price of the bond without any compensation of accrued interest, so keep in mind if you are purchasing a bond off the secondary market. The dirty price is the actual price you will be paying in cash.

But if the terms coupon and par value are too confusing, then you’re probably better off just sticking to the simple SSBs — which actually references 1, 2, 5 and 10-year SGS bonds as a benchmark to compute its interest rates. In addition, early redemption for SSBs is easily done via iBanking/ATMs and not on the stock market like for SGS bonds.

However, the trade-off is that you cannot make a profit off the price fluctuations in the secondary market.

This is exactly why SSBs were created, to give Singaporeans access to bond-investing — without its complexities.